The Kalahari Desert

The desert is part of the 970,000-square-mile Kalahari Basin, which includes the Okavango River Delta and other wetter areas. The basin encompasses virtually all of Botswana and more than half of Namibia. The Kalahari sand dunes, some of which stretch west to the Namib Desert, compose the largest continuous expanse of sand on earth. That is because although the Sahara Desert is larger overall, sand dunes make up only about 15% of its area. These dunes are covered with a relative abundance of vegetation, including grass tussocks, shrubs, and deciduous trees that have evolved to make use of the area's infrequent precipitation and wild swings in temperature. In summer, the heat can top 45 degrees Celsius (115 degrees Fahrenheit); on winter nights, lows can drop to -15 degrees Celsius (seven degrees Fahrenheit).

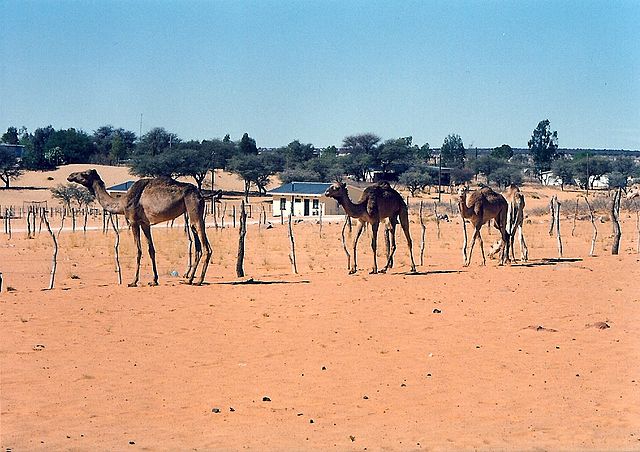

In the wetter north and east, open woodlands exist, made up mainly of a type of acacia known as the camelthorn tree. Endemic to the Kalahari, the camelthorn is a crucial part of the desert ecosystem, manufacturing nutrients that encourage other plants to grow around its base and providing shade for animals.

Other trees that grow in this area include shepherd's tree, blackthorn, and silver cluster-leaf. In the drier southwest, vegetation and wildlife are much more sparse, but Hoodia cactus - used for thousands of years by the San people to ease hunger and thirst during long hunting trips - still maintains a foothold there. Flora and faunaAnimals that have adapted to the extremely dry conditions in the Kalahari include meerkats; gemsbok, a large member of the antelope family; social weavers, a type of bird; and the Kalahari lion. The Kalahari's endemic wildlife species have adapted either to survive many days without water, or to obtain water from plants. Many reptiles also live in the Kalahari, including Cape cobras, puff adders, and rock monitors. Numerous other birds and mammals utilize the desert, but most are migratory, venturing into the Kalahari only when adequate water is present. In addition to the Hoodia cactus, other edible plants - used by both animals and humans - include creeping tsamma melons, gemsbok cucumbers, and wild cucumbers.

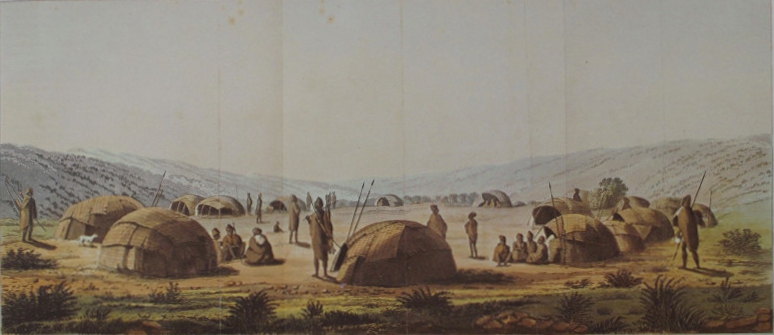

Indigenous population

Their continued presence—and the desire of many San to return to their traditional way of life in the desert—has sparked major disputes with the Botswanan government over indigenous rights to hunt and live within the boundaries of national parks and protected areas. One San group, the Basarwa, won the right to live within the Central Kalahari Game Reserve in 2006. Disputes have continued, however, over water rights—particularly whether the San can tap a well within the reserve that was drilled by the world's largest diamond-mining company, De Beers, when it was prospecting in the area in the 1980s. In addition to diamonds, deposits of nickel, copper, and coal have been discovered within the Kalahari, though most of these remain undeveloped. Livestock grazing is considered the largest threat to the Kalahari ecosystem, as it has resulted in changes to plant communities and increased erosion, but even this practice remains relatively limited. The largest protected areas within the Kalahari are the adjacent Central Kalahari and Khutse game reserves in Botswana, and the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, which joined South Africa's Kalahari Gemsbok National Park and Botswana's Gemsbok National Park to create the continent's first Peace Park in 2000. Kgalagadi, which means "place of thirst," covers 15,000 square miles in and around the Kalahari.

|

|

|

|

||

| © Kalahari Desert - All rights reserved! |

.jpg)

Today, few San survive exclusively by hunting and foraging; many have adopted sedentary

lifestyles in towns. However, about 100,000 members of this ethnic group still live along the fringes of the

Kalahari.

Today, few San survive exclusively by hunting and foraging; many have adopted sedentary

lifestyles in towns. However, about 100,000 members of this ethnic group still live along the fringes of the

Kalahari.